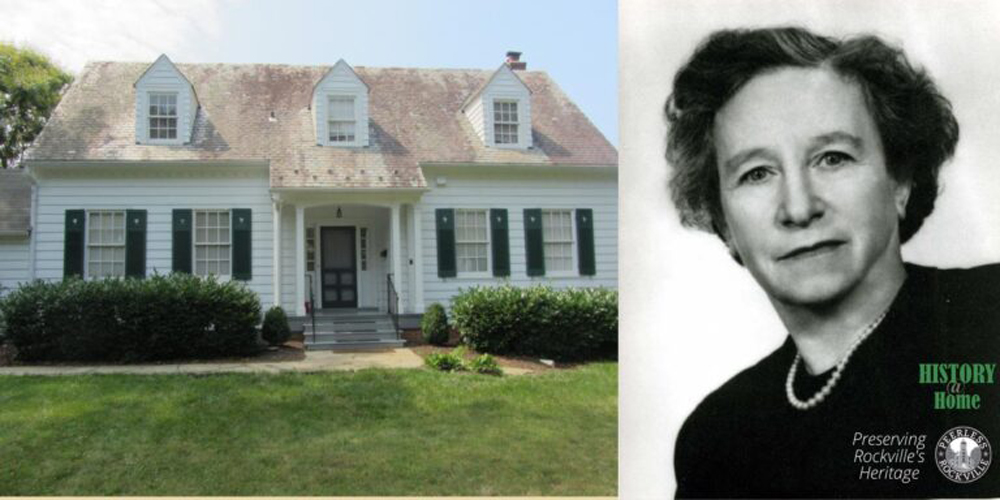

When the National Park Service went looking for landmarks to highlight women’s history in the United States, it found its way to a German-born Jewish psychiatrist who escaped the Nazis in 1933 and settled in Rockville, Maryland.

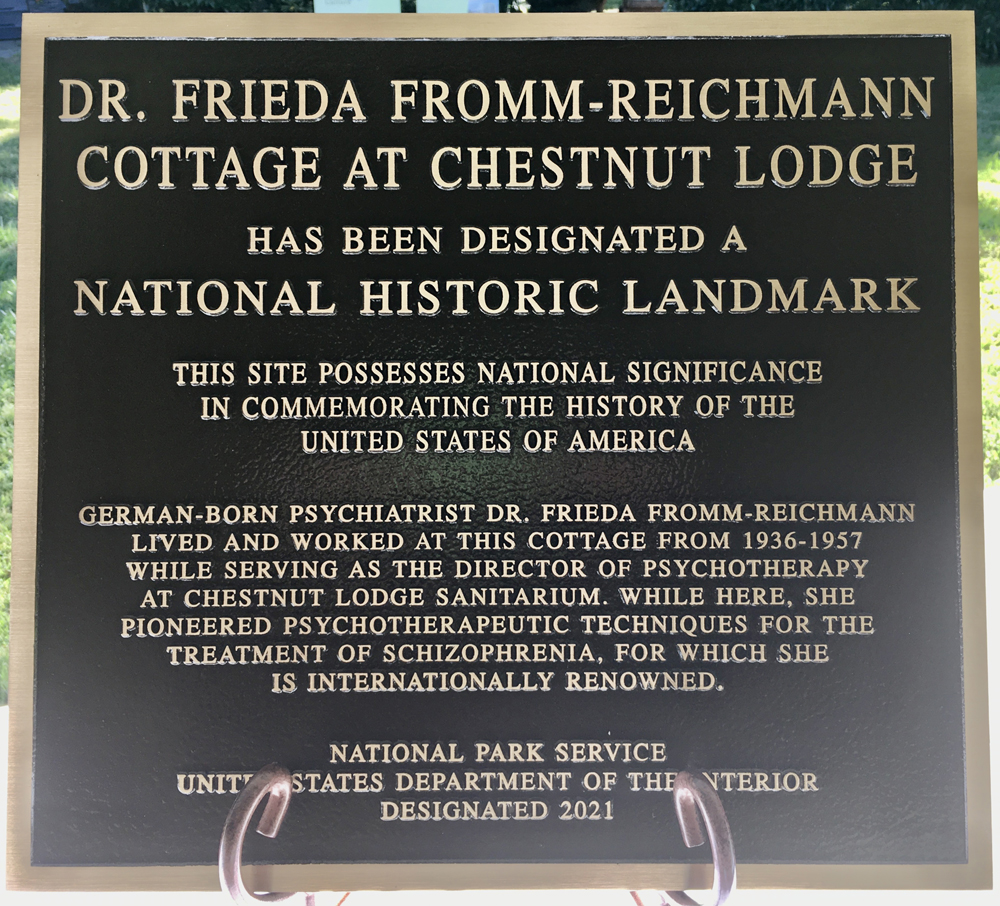

Her name was Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, world renowned for her pioneering work with schizophrenia patients at Chestnut Lodge, the one-time mental hospital on Rockville’s West Montgomery Avenue.

While the actual sanitarium burned down in 2009, the cottage built for Frieda in 1936 survived “by divine miracle,” as her biographer Dr. Gail Hornstein puts it.

Hornstein spoke on a crisp sunny October 1, when about 100 people gathered at Frieda’s Cottage to formally celebrate its designation as a US National Historic Landmark.

The event culminated Peerless Rockville’s 14 years of efforts to restore Frieda’s Cottage and brought renewed focus to Dr. Frieda Fromm-Reichmann and her insistence that severely disturbed patients could be healed. The house at 19 Thomas Street is a short one-mile walk from New Mark Commons.

It is a “compelling story of women in science and the import of mental health,” said Sherry Frear at the dedication. Frear is the chief and deputy keeper of the National Register of Historic Places and the National Historic Landmarks Program at the National Park Service. The designation puts Frieda’s Cottage on the rarefied list of 2,621 National Historic Landmarks. (Our neighborhood New Mark Commons, on the other hand, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, a compilation of about 96,000 properties nationwide.)

The cottage was donated to Rockville’s historic preservation organization, Peerless Rockville, by the developer who purchased the large Chestnut Lodge property and built dozens of new homes there. The donation was accompanied by a gift of $100,000 to help with restoration.

New Mark resident Sima Osdoby, former Peerless executive director, talks to Eileen McGuckian, historian and preservationist.

Dick Stoner, president of the Peerless Board of Directors, is credited with leading much of the restoration effort. The cottage had been used as offices for many years and needed a lot of work.

“People donated multiple Saturdays,” Stoner said. “We had tremendous cleanup days.” He noted that Maryland Historical Trust had provided additional financial assistance with a revolving fund that helped install heating, air conditioning and plumbing.

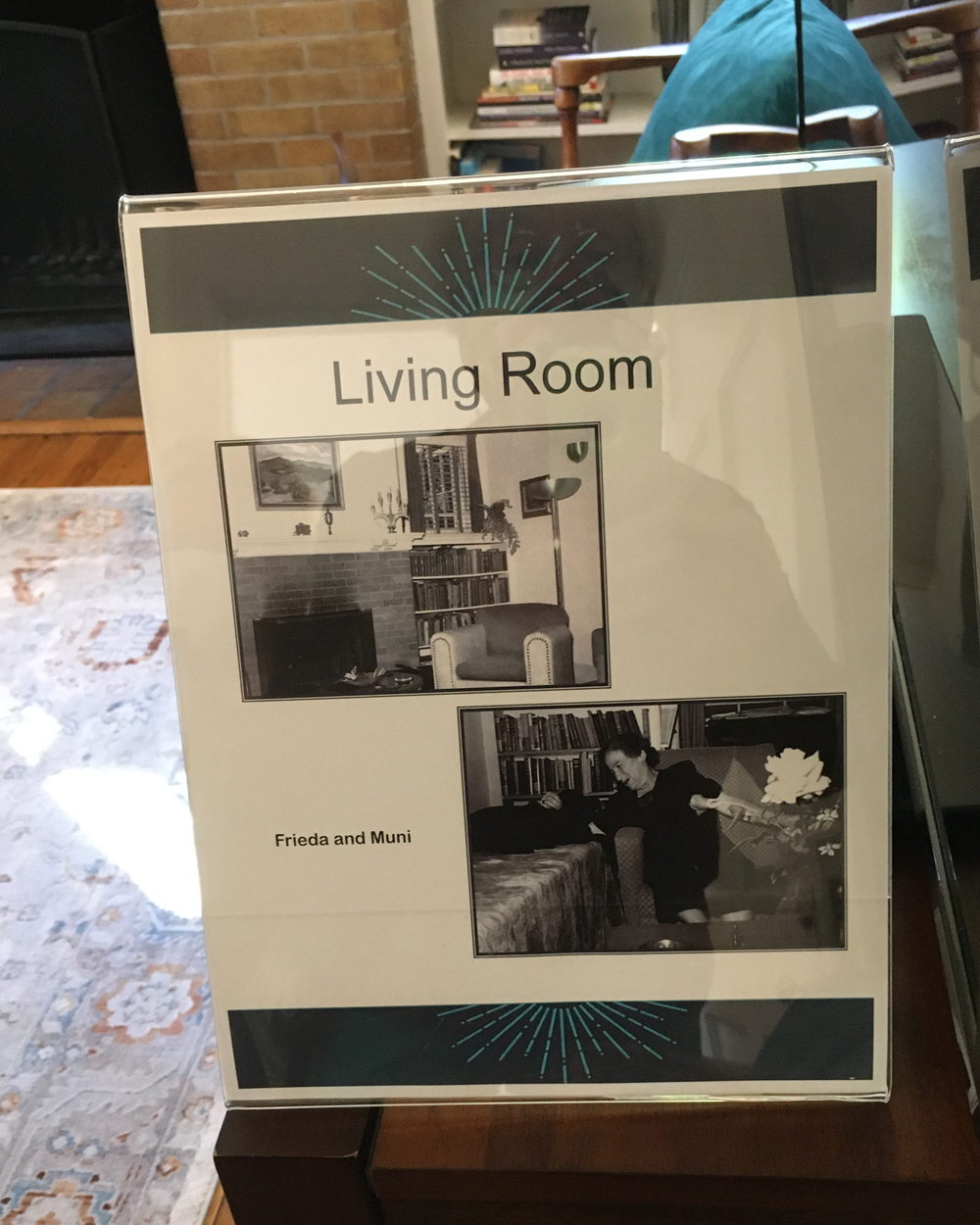

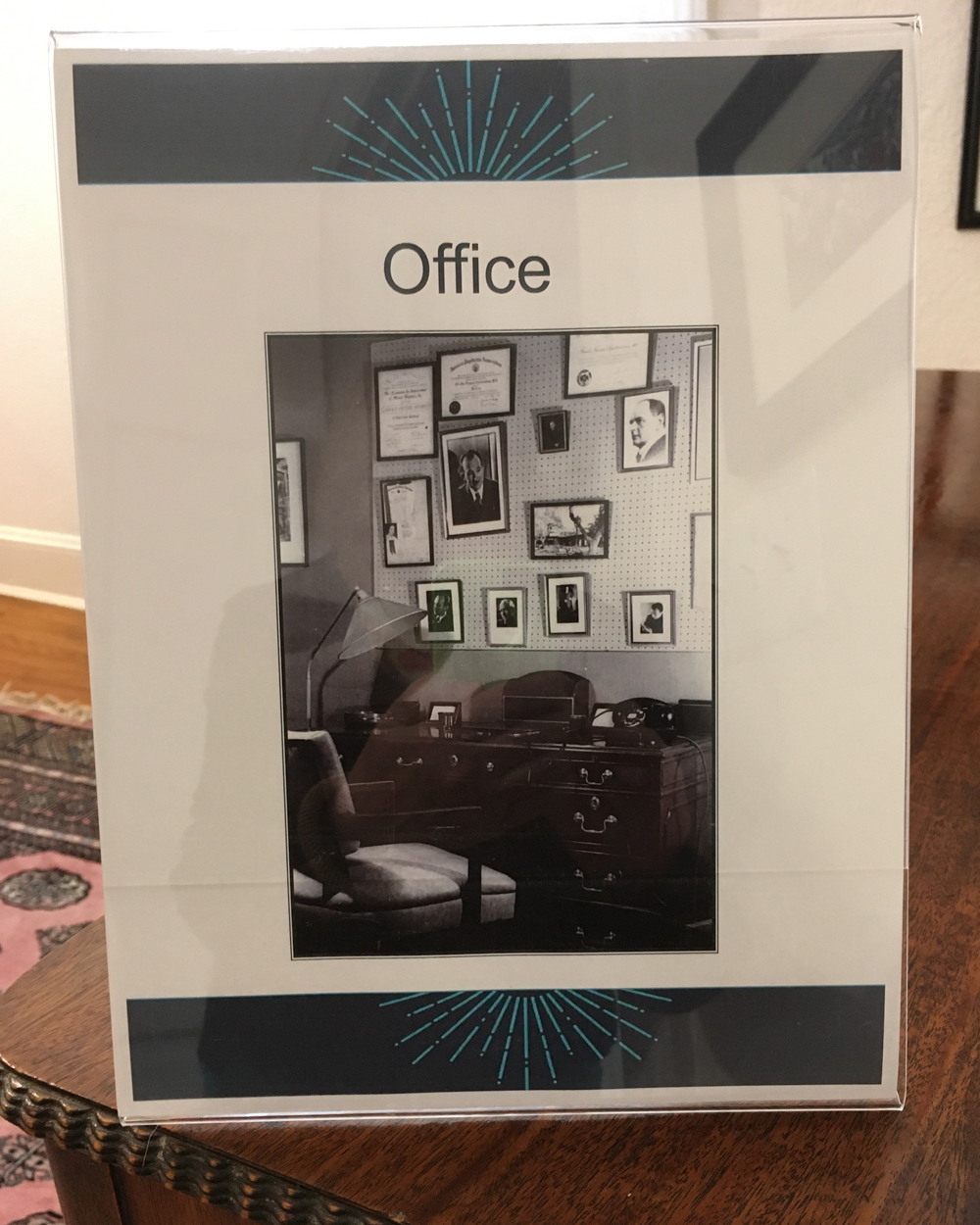

Today, the cottage is rented out as a residence with income going to Peerless Rockville. According to the National Park Service, the residence is to be open to the public five days a year. October 1 was one of those days, and people stood in a long line waiting for the tour. Frieda saw many patients at the cottage, and visitors could see the room where patients were received and the room where she treated patients, which is now a bedroom.

Waiting for a glimpse inside Frieda’s Cottage

Who was Frieda Fromm-Reichmann?

Hornstein, professor of psychology at Mount Holyoke College, held the Rockville audience rapt for 45 minutes with Frieda’s story. She spent ten years researching the biography published in 2000, To Redeem One Person is to Redeem the World: The Life of Frieda Fromm-Reichmann.

Born in 1889 in Karlsruhe, Germany, Frieda Reichmann was one of the first women admitted to medical school in Germany, in Konigsberg, graduating in 1914—just as World War I broke out, bringing with it new and more devastating artillery and trench warfare resulting in an unprecedented number of brain injuries.

Dr. Reichmann was drafted to work with soldiers whose brain injuries were “completely different from what doctors had trained for,” Hornstein said. What she and her mentor, Dr. Kurt Goldstein, found was that each soldier invented different ways to deal with his injuries. Each patient had a unique pattern of symptoms—laughing, crying , moving with jerkey bursts, etc.

Frieda found that it was “up to the physician to figure out what the patient could or couldn’t do,” Hornstein said.

Up until her exile, Frieda was instrumental in founding psychiatric institutes in Germany as a practitioner and teacher. One of her student/patients was Erich Fromm, the social psychologist and psychoanalyst who was undergoing psychoanalysis with her as part of his own training. They would later marry, and the partnership was key to her survival from Nazi persecution of Jews.

Getting word in 1933 that she was targeted for arrest, Fromm arranged for her escape with “two tiny suitcases” to the United States. She soon started work as a summer replacement at Chestnut Lodge, ending up staying there to help develop “the only hospital ever to specialize in the psychotherapy of psychotic patients,” as Hornstein describes the institution in her biography.

“Frieda had an unusual ability to connect to severely disturbed patients,” Hornstein said. “She did what Freud thought was impossible.”

“She often sat by the beds of her most disturbed patients, sometimes staying on the ward all night long … She was convinced that inside the avalanche of illness was a terrified person crying out for help. Her job was to get that person out,” Hornstein said.

She thought psychiatrists who drugged or kept people in restraints got what they asked for—patients who made little progress.

Dr. Fromm-Reichmann’s work is still talked about “in hushed tones” by students and practitioners of psychiatry, Hornstein said. Her seminal work published in 1950, Principles of Intensive Psychotherapy, is still widely used in the field.

After Frieda’s arrival in the US, Chestnut Lodge owner Dr. Dexter Bullard convinced her to stay by building her the cottage, where she lived from 1936 until her death in 1957 at age 67. Her work and her lectures in Washington and New York “inspired a whole generation of psychiatrists to create truly therapeutic environments for people previously assumed to be beyond reach,” Peerless Rockville says in its brochure.

Frieda often saw patients up to 10 p.m. on a daily basis, and her work brought patients from near and far whose families were “desperate and willing to try anything.” The only alternative for many patients and families in the Washington area was the controversial practice of lobotomy by Dr. Walter Freeman at George Washington University—a man who was practicing surgery without surgical training and was later banned from doing the operations.

Frieda’s Fame in Fiction

Hornstein noted the irony that Frieda was long a presence in American culture, even if not recognized as such. She was the model for the fictional physician in the 1964 bestseller, “I Never Promised You a Rose Garden,” an account of a teenage girl’s battle with schizophrenia, based loosely on the experiences of the author Joanne Greenberg and written under the pen name of Hannah Green. A film and a play were later based on the book. A song co-opted the book’s title but appears to have had little to do with Frieda.

The National Landmark designation comes the same year as the appearance of another novel—this one by local author Ellen Prentiss Campbell, Frieda’s Song. The story deals with mental illness through time flashbacks between a modern-day family renting the cottage and Frieda’s own life in the cottage.

For Frieda’s biographer, the dedication of the Cottage was a “thrilling moment.”

For Frieda’s biographer, the dedication of the Cottage was a “thrilling moment.”

“It almost seems like Frieda could walk through the house and out again and feel at home,” said Nancy Piccard, executive director of Peerless Rockville, at the dedication. “I think she would have been a little bit confused by all the fuss.”

Eds Note: Full Disclosure: The writer is a member of Peerless Rockville.

- Read the National Park Service’s document on the designation.

- To support Peerless Rockville and Frieda’s cottage, go to: peerlessrockville.org.